On Zephyr’s Wings: NASA Restarts Venus Exploration

Credit: NASA/JPL

When Leonardo Da Vinci first dreamed of flight in the 15th century, it would have been near inconceivable to him that his namesake would make it to the stars – but that’s exactly what’s happened. The Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gasses, Chemistry, and Imaging, or DAVINCI mission, is a groundbreaking new approach to studying Earth’s sister planet, one which truly embodies the polymath’s ideology of revolutionary new ideas. DAVINCI will carry his legacy to the cosmos, employing new ideas to study Earth’s strange sister. This mission, launching in 2029, is set to revolutionize our understanding of the Solar System and paint a clearer picture for future explorers to Venus. The measurements taken by DAVINCI will investigate the possible history of water on the planet and the chemical processes at work in the poorly understood lower atmosphere. Before it reaches the surface, the DAVINCI probe will capture high-resolution images of regions of the planet’s ridged terrain known as tesserae, returning the first images of the planet’s surface since the Soviet Venera 14, which landed in 1982. We at Space Scout were very fortunate to sit down with the mission’s Principle Investigator, Dr. James Garvin, and learn more about this historic mission.

DAVINCI, in its current form, has existed for some time, but was only selected as a finalist and winner for the Discovery program on June 2, 2021 alongside its sister mission, VERITAS. It is set to be the first American mission to Venus since the highly successful Magellan mission, which ended its mission in 1994 after conducting a thorough radar survey of the planet. Since then, international explorers have made efforts to understand our mysterious neighbor. Dr. Garvin described the selection as “asking the correct questions for the scientific community, and lining them up to when they needed to be asked.” This motivation pushed the DAVINCI team to propose the mission in a variety of forms four times, before ultimately getting selected as Discovery 15.

Credit: NASA/Goddard

DAVINCI consists of not one, but two spacecraft working in tandem to maximize the scientific output of the mission. The first, the Carrier Relay Imaging Spacecraft, or CRIS, will act as the first phase of scientific operations during two flybys of Venus. Launch for the mission is currently scheduled for 2029, atop a launch vehicle not yet selected. While the mission is heading for an interplanetary destination, the trajectory is fairly low energy, resulting in greater flexibility for mission architecture and launch vehicle selection. After separation from the launch vehicle, DAVINCI will rely on CRIS to provide power and propulsion for the lander, and to enable a precisely targeted landing after the initial survey is complete. While other landing missions have launched directly to their intended target, Venus’ slow rotation rate necessitates a 2 year cruise phase, coupled with two flybys to ensure that lighting at the landing site is ideal for the science conducted by the Descent Probe. In 2031, CRIS will separate from the Descent Probe and fly by the planet for a third time, acting as a communications relay for up to 107 minutes as the primary atmospheric science phase is completed. While not required as part of the baseline mission objectives, CRIS will have enough propellant onboard to potentially return to Venus and enter orbit. This phase of the mission is not as clear, as the health of CRIS and the readiness of followup missions will determine the spacecraft’s future.

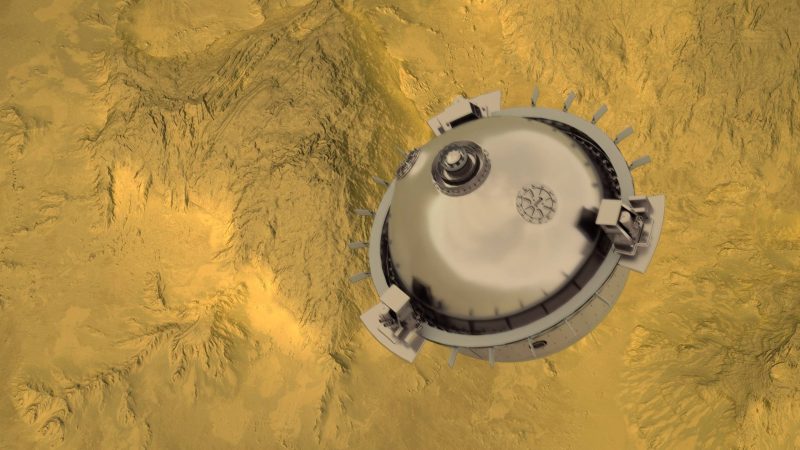

The Descent Probe, known internally at Goddard as Zephyr, is designed to encounter an environment unlike any other in the solar system – an “ocean of air,” as described by Dr. Garvin. Zephyr, subject to renaming as the launch date grows closer, is designed to act as a mobile science lab as it descends through the skies of Venus, with the goal of measuring the gasses and other compounds that make up the atmosphere. After separation from CRIS, Zephyr will rely on the Probe Flight System to carry it through the harshest part of entry. Based on legacy hardware from other Lockheed Martin built systems, the 100 inch diameter heat shield will bear the brunt of the entry interface before separation of the heat shield and back shell. The relationship between Goddard Space Flight Center and Lockheed Martin is described by Dr. Garvin as a symbiotic one, building on legacy systems mastered for missions like OSIRIS-REx. Once the work of the Probe Flight System is complete, and the backshell and heat shield are separated, DAVINCI will deploy its parachute system, helping to arrest the descent and extending time in the upper atmosphere before separating for its final leg of the journey.

Credit: NASA/Goddard

Even as Zephyr descends through the atmosphere, it will be hard at work performing a variety of science tasks. The Venus Atmospheric Structure Investigation, or VASI, will perform the mission’s first survey of Venus’ atmosphere. The system will conduct measurements of gas through a number of vents, performing these measurements once every 10 seconds throughout descent. As Zephyr ditches its parachute after arresting its velocity, a second set of vents will open to allow the probe to investigate the noble gasses in the atmosphere, which Dr. Garvin described as the “fossils of the solar system’s formation.” As Zephyr descends further into the atmosphere, and the surface starts to become visible, the imaging system will begin to snap photos – 550 of which are planned throughout the 90 minute mission. The camera, known as VenDI or Venus Descent Imager, will sit behind a 14 cm sapphire window, designed to withstand the extreme environment of the lower Venusian atmosphere. The spacecraft, as it descends further through the clouds, will begin to encounter the harshest environments of the mission – crushing atmospheric pressure and corrosive gas make survival in this regime incredibly challenging. The focus during this regime will be both sampling and imaging, with the goal of understanding the local environment in as much detail as possible.

While the mission is not intended as a lander, there is a possibility that the vehicle could survive its descent through the atmosphere and land intact on the surface. If this were to occur, the mission would enter a new phase – one to maximize the science return over the precious 17 minutes of relay time remaining. This phase, should the mission reach this point, will see the vehicle upload all of the images it has onboard, and continue to sample its local environment with the intention of possibly sampling elements of the soil. After 17 minutes, the line of sight connection with CRIS will be lost, and Zephyr will likely have been destroyed. DAVINCI has a fundamental distinction from previous robotic NASA missions: while rovers and orbiters are often designed for a series of mission extensions, DAVINCI’s mission duration is both fixed and finite. The 90 minutes of descent will be all the team has to gather as much data as possible, acting as a pathfinder for other missions to follow.

Dr. Garvin described DAVINCI, as well as its companion spacecraft VERITAS and EnVISION, as part of a “new Venus rising” in the field of planetary science: a revolutionary new look at Earth’s strange sister. For 29 years at the time of writing, not a single American spacecraft has visited Venus with the intention of exploring it in detail. This will change throughout the 2030s, a timeframe Dr. Garvin refers to as the “decade of Venus”, as these new robotic missions aim to expand humankind’s understanding of the planet. Despite budgetary concerns and systematic issues within the agency, Dr. Garvin’s confidence in these missions producing incredible data remains steadfast. With the backing of the decadal survey, the agency’s commitment to Venus exploration is strong, and the scientific community’s quest to understand the Solar System only further drives the need for missions like DAVINCI. With launch now only 6 years away, scientists on Earth can begin to wonder what they’ll encounter in this ocean of air.

Edited by Scarlet Dominik and Beverly Casillas